In 2014, Indonesia officially joined the ranks of countries providing national health insurance for its citizens. This milestone marked the culmination of a series of significant transformations within Indonesia’s healthcare system, resulting in the establishment of one of the world’s largest single-payer health insurance systems.

Previously, health insurance programs in Indonesia were largely sectoral in nature, offering coverage only to specific groups such as civil servants, military personnel, and workers in the formal economic sector. The introduction of the Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN) in 2014 expanded access to health insurance, ensuring coverage for all Indonesians.

Within four years of its implementation, the JKN program had reached nearly 75% of Indonesia’s population, or approximately 203 million people. By 2024, the JKN system had entered its tenth year of implementation, making this an opportune moment to critically evaluate its achievements, progress, and the challenges that may hinder its execution and effectiveness.

Nationwide Improvement in Health Indicators

The introduction of the JKN program in 2014 can be contextualized within a healthcare environment that has shown continuous improvements in its indicators. As illustrated in the table below, two years prior to the launch of JKN, life expectancy in Indonesia had been increasing slowly but steadily since 1990.

Several interventions and policies began to yield results, as indicated by improvements in key health indicators, between 1990 and 2012, life expectancy at birth rose from 63 to 71 years, while the infant mortality rate declined from 62 to 26 per 1,000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate dropped from 85 to 31 per 1,000 live births during the same period.

This reflects a positive trajectory in improving overall health outcomes in Indonesia. The country has made significant progress in reducing the prevalence of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) and influenza.

However, major challenges persist in other health indicators. While the burden of communicable diseases has declined significantly, the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as stroke and diabetes, has risen sharply. Maternal mortality remains a critical issue, with a rate of 359 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Similarly, childhood stunting continues to affect 31% of children under five years old, and TB remains a significant threat, with over one million new cases annually.

Additionally, the growing prevalence of NCDs is a serious concern. Obesity rates have more than doubled, increasing from 10% in 2007 to 21% in 2016, while cases of diabetes have surged by 63% since 2005. These trends underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions and comprehensive health policies.

Largely due to the JKN system, empirical studies have demonstrated that citizens, regardless of their socioeconomic status, now have access to higher-quality healthcare compared to the years prior to JKN’s implementation. The pre-JKN disparities, which had favored middle- and upper-income groups, have been partially reduced.

Data on hospital utilization by JKN members compared to non-members further highlights this shift. The table below illustrates an increase in hospital admission rates among the poorest quintiles, reflecting improved accessibility driven by government subsidies and a focus on underserved areas.

Data1 also indicates that the JKN program has contributed to improved health outcomes for Indonesian citizens. A study conducted by a team of academics at Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, comparing data from before and after the implementation of JKN, revealed a decline in mortality rates from neurological diseases and strokes following the introduction of the program.

The Financing Aspect of Universal Health Coverage

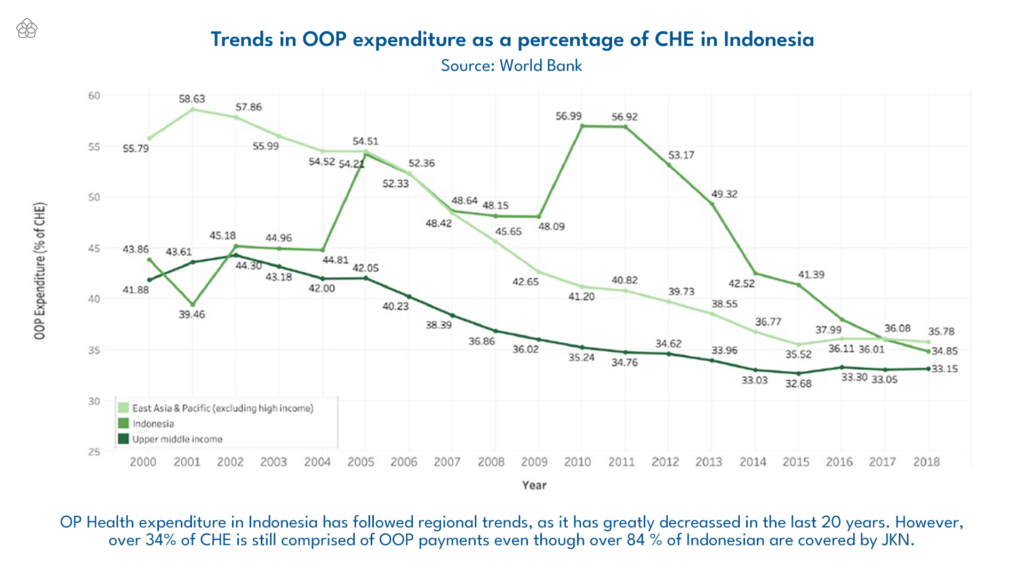

A core principle of UHC is to minimize out-of-pocket spending by individuals requiring healthcare services. In this regard, the JKN program has demonstrated progress, although it has not yet fully achieved this goal, as illustrated in the table below.

Although the JKN program has provided nearly free access to healthcare services, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures still accounted for 27.5% of the country’s Total Health Expenditure (CHE) in 2021.

While this marks an improvement from 34.76% in 2019, it remains significantly higher than the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended threshold of 20%.

The majority of these OOP expenditures are driven by costs related to pharmaceuticals and healthcare services. On average, Indonesians spend IDR 32,168 per month on healthcare. Interestingly, spending on preventive measures has increased to 29% of total monthly healthcare expenditures, reflecting a growing awareness of the importance of prevention.

Medical check-ups (MCUs) account for 34% of preventive spending, a significant rise compared to previous years, highlighting an increased focus on proactive health monitoring.

Other components, such as fitness, massages, vitamins, and traditional herbal remedies (jamu), also contribute to this trend of preventive action. This positive shift is expected to benefit the healthcare industry in the long run.

In the context of regional healthcare funding standards within ASEAN, Indonesia’s per capita health expenditure remains among the lowest, surpassing only countries with considerably lower national incomes, such as Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos.

The chronic underfunding of the healthcare sector is evident from the fact that only 3–5% of Indonesia’s GDP is allocated to public health—a percentage that has been steadily declining, particularly due to budget cuts related to the pandemic. This figure lags far behind the regional average of approximately 9%.

To meet the health targets outlined in the 2020–2024 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN), the government estimates that a total budget of IDR 371.3 trillion will be required for primary healthcare services.

This projected cost has steadily increased each year, from IDR 62.4 trillion in 2020 to IDR 85.4 trillion in 2024. However, the government’s healthcare budget allocation remains imbalanced, with 78% directed toward curative services and only 10% allocated for preventive measures.

The Future Direction of the JKN Program: Expanding Coverage and Improving Financing

As discussed earlier, the JKN program has successfully expanded healthcare access to millions of Indonesians. However, the narrative shifts significantly when the discussion turns to the overall quality of the program. Expanding healthcare coverage for the population does not automatically equate to providing high-quality healthcare protection.

At its core, the most significant issue within the JKN program lies in its continuity of coverage. Only the poorest and wealthiest segments of the population are consistently receiving adequate healthcare protection.

By 2024, BPJS (the implementing agency for JKN) had reached 98.67% of the population, or more than 277 million people. Yet, despite its goal of universal coverage, the implementation of BPJS remains uneven and faces various challenges.

The primary challenge in expanding BPJS coverage is the “missing middle”—a segment of the population that is neither categorized as poor nor employed in the formal sector. Many in this group work in the informal economy and do not automatically receive government-subsidized healthcare coverage, meaning they are expected to register voluntarily and pay premiums independently.

However, informal workers in this category often have unstable incomes, making it difficult for them to commit to regular contributions. Without adequate social security protection, this group remains vulnerable to financial shocks and lacks safety nets for old age or unforeseen events.

Despite efforts to broaden coverage, much of this group remains uninsured due to low rates of voluntary registration. BPJS has made significant progress in expanding insurance coverage among formal sector workers, who now constitute the majority of program participants.

By 2018, the program had enrolled 28 million active participants from the formal sector. However, the situation is drastically different for informal workers, who comprise a large portion of the labor force.

Despite their numbers, only 2.4 million informal workers actively contributed to the program during the same period. This means that less than one-quarter of the productive working-age population—estimated at over 150 million people—has access to healthcare services provided by BPJS.

Indonesia’s social security system inherently prioritizes workers in the formal sector over those in the informal sector. Law No. 40/2004 on the National Social Security System outlines five main schemes: health insurance, occupational accident insurance, life insurance, old-age savings, and pensions.

Although these schemes are comprehensive, their coverage is primarily geared toward formal sector workers. Informal workers, particularly those in the “missing middle,” face numerous barriers to participation. These include rigid contribution requirements, limited program flexibility, and insufficient outreach to rural and underserved communities.

Additionally, regulations require participants to register for multiple schemes, such as occupational accident insurance and life insurance, as prerequisites for accessing old-age savings programs. While this approach ensures comprehensive coverage for formal sector workers, it creates a financial burden for informal workers with limited resources.

Furthermore, informal workers remain ineligible for pension programs, leaving them without essential retirement savings for the future. A study conducted by the University of Indonesia and the Australian National University highlighted that low insurance literacy is a major barrier for informal workers. Expanding financial literacy campaigns is essential to help individuals understand the benefits of health insurance and the long-term risks of remaining uninsured.

Even outside the “missing middle” group, many JKN participants still face significant challenges, particularly regarding the quality of services provided through the program.

Structural issues, such as disparities in healthcare service availability and infrastructure, demonstrate that insurance coverage alone does not guarantee accessibility, reliability, or high-quality care. Without addressing these fundamental issues, merely offering insurance options may not be sufficient to encourage broader participation in the system.

The rapid increase in BPJS membership has placed immense pressure on Indonesia’s healthcare infrastructure, particularly at the primary care level. Domestically, Indonesia suffers from a healthcare infrastructure shortage, with only 1.49 hospital beds per 1,000 people as of 2021—one of the lowest rates in the ASEAN region.

Additionally, the country faces a shortage of medical professionals, with a doctor-to-population ratio of just 0.6 per 1,000. This figure is far behind neighboring countries such as Malaysia (2.2 per 1,000) and Thailand (0.95 per 1,000).

Although 82% of government hospitals were deemed adequately prepared in 2017, only 67% of community health centers (puskesmas) met basic readiness standards. Low-quality services, drug shortages, and a lack of medical specialists—particularly in rural and remote areas—continue to hinder the effectiveness of the JKN program. Inadequate readiness at primary care facilities exacerbates unnecessary referrals to advanced hospitals, driving up costs and reducing system efficiency.

Another critical challenge lies in strengthening partnerships with healthcare facilities. While many providers have joined the program, some larger and more advanced hospitals have declined to participate, citing inadequate service tariffs. Conversely, smaller hospitals often lack the resources or infrastructure to meet BPJS partnership standards.

Socioeconomic disparities in Indonesia remain stark. Wealthier patients have the means to seek medical treatment abroad. In 2022, an estimated one million Indonesians traveled overseas for healthcare services, primarily to Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, and the United States, with total expenditures reaching approximately IDR 165 trillion (USD 9.7 billion). However, this option is unavailable to lower- and middle-income groups, who face financial and access constraints when seeking healthcare services domestically.

In terms of primary and secondary healthcare services, accessibility disparities further highlight systemic inequalities. Research indicates that while primary care utilization is relatively equal across educational levels, preventive services requiring greater sophistication—such as cholesterol tests, blood glucose tests, and electrocardiograms (ECGs)—are disproportionately accessed by individuals with higher education and income levels.

This trend underscores financial barriers and a lack of information preventing lower-income and less-educated groups from fully utilizing preventive healthcare services.

These socioeconomic stratifications become even more apparent in secondary and inpatient healthcare services. Individuals from higher education and income groups are more likely to access these services, while those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face significant obstacles, including financial constraints, informational gaps, and perceptions of inadequate service quality or relevance.

Beyond structural disparities, Indonesia’s healthcare system also suffers from outdated data and information systems. Fragmented health information systems (SIKNAS and SIKDA) and incomplete vital registration hinder effective monitoring, evaluation, and resource allocation.

Limited reporting from the private sector, inconsistent data integration, and insufficient digitalization further obstruct timely decision-making. While initiatives such as the Indonesia Mortality Registration System Strengthening Project and the Early Warning Alert and Response System have shown gradual progress, a fully integrated and robust health information system remains unrealized.

To address the widening gaps in Indonesia’s healthcare system, the government must tackle financial and governance issues simultaneously. Strengthening governance is a key pillar that, when combined with improved financing, could fundamentally transform Indonesia’s healthcare infrastructure.

The Indonesian government has sought to undertake comprehensive reforms to the healthcare system through the 2023 Health Law, aiming to promote more equitable, inclusive, and high-quality healthcare services. Article 401 of the law emphasizes the importance of diversifying funding sources in the healthcare sector.

In this context, closer collaboration between the public sector, private institutions, and civil society organizations is necessary to ensure that available resources are used effectively and efficiently to achieve the ultimate goal of equitable healthcare services.

Furthermore, to enhance the efficiency of healthcare financing, the government has abolished the previously mandated spending framework, granting greater autonomy in financial management and enabling the implementation of performance-based budgeting.

These reforms aim to address healthcare challenges through an approach based on disease burden and epidemiological studies, while allowing for budget allocation that is responsive to actual needs without being constrained by pre-set financial limits.

To optimize the allocation and utilization of healthcare funds, the government is promoting the development of the Health Sector Master Plan (RIBK), as outlined in Article 409. This strategic tool is designed to ensure alignment of healthcare development priorities by integrating resources from governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, including the private sector and civil society.

This framework is expected to facilitate more equitable distribution of healthcare services. Given the limited funding in the healthcare sector, the RIBK framework will be key to driving governance reforms, enhancing transparency, and ensuring the prudent utilization of healthcare resources

Recommendations for Future Policy Directions

The Indonesian government should consider shifting its healthcare focus from an overemphasis on curative services to strengthening preventive healthcare measures. In 2017, former Minister of Health Nila Moeloek warned that the rapid pace of urbanization, coupled with disparities in healthcare quality between regions, poses a significant risk of overwhelming Indonesia’s healthcare system2.

This is further exacerbated by the simultaneous rise of non-communicable diseases, communicable diseases, and seasonal illnesses, all of which continue to burden the system. Additionally, unhealthy lifestyles and environmental degradation in Indonesia have worsened the situation.

Nila Moeloek also emphasized that a large portion of national healthcare spending under JKN is allocated to managing long-term NCDs. She advocated for prioritizing preventive healthcare measures, as preventing diseases is far more cost-effective than treating them.

In its current form, the JKN system is unlikely to sustainably meet the treatment needs of Indonesians with NCDs, given the high medical costs associated with these conditions. This is evident in BPJS’s annual reports, which consistently highlight the growing dominance of NCDs in healthcare expenditures. Specifically, heart disease, cancer, and stroke accounted for IDR 19.8 trillion (~€1.1 billion), or approximately 90% of total healthcare claims.

Given this reality, it is essential for the JKN system not only to redesign its governance and financing structures but also to incorporate a stronger focus on what health policy researchers term “universal risk coverage.”

This approach emphasizes early detection of risk factors that can lead to NCDs3. At the most basic level, government interventions could include implementing taxes on high-sugar products or increasing tobacco taxes to encourage healthier lifestyle choices among the population.

Therefore, the future direction of Indonesia’s healthcare system lies in balancing curative services with preventive and promotive strategies. Such an approach will not only reduce the overall healthcare cost burden but also sustainably improve the population’s quality of life.

- Rina Agustina et al., “Universal Health Coverage in Indonesia: Concept, Progress, and Challenges,” The Lancet 393, no. 10166 (December 19, 2018): 75–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31647-7. ↩︎

- Moeloek, Nila F. 2017. “Indonesia National Health Policy in the Transition of Disease Burden and Health Insurance Coverage” Medical Journal of Indonesia 26 (1):3-6. https://doi.org/10.13181/mji.v26i1.1975. ↩︎

- Agustina et al., “Universal Health Coverage in Indonesia: Concept, Progress, and Challenges.” ↩︎